To better understand the molecular mechanisms that underlie ALS, researchers at the Les Turner ALS Center at Northwestern Medicine are harnessing the power of one of the 21st century’s most powerful medical tools: stem cells.

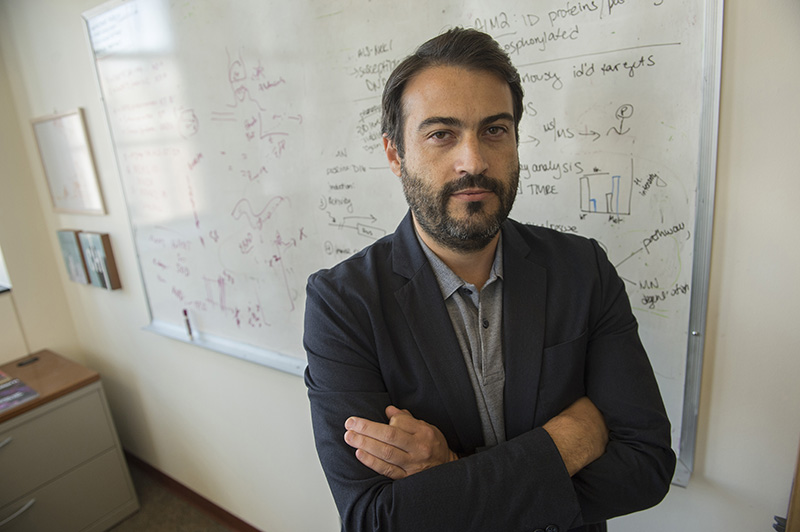

In the lab of Evangelos Kiskinis, associate professor of neurology and neuroscience at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, the research team is developing a new technological platform to study stem cells derived from people living with ALS.

These stem cells, called induced pluripotent stem cells, are created by taking a blood sample and applying a cocktail of molecular factors to it. That cocktail turns the blood cells back into embryonic stem cells, which can then be grown into any kind of human cell.

In Kiskinis’s lab, the research team has been using this technology to study inherited forms of ALS. However, about 90 percent of ALS cases are considered sporadic, which means they occur at random and aren’t associated with a family history.

In some ways, inherited diseases can be easier to study. These diseases are often linked to a specific gene mutation, and researchers can just replicate that mutation in the lab and study its effects. But since sporadic ALS likely occurs from a combination of gene mutations and environmental factors, it’s harder for scientists to understand just how the disease develops.

To find out, Kiskinis and his team are building innovative cellular models by “pooling” together stem cell lines derived from multiple ALS patients. These cells have been grown into motor neurons, and the team is now interrogating the molecular functions of those neurons through an array of approaches. The eventual goal is to do this with hundreds of stem cells from people living with sporadic ALS.

To find evidence of a certain molecular pathology associated with ALS, the team looks for evidence of disruptions in RNA signatures. To better understand how the disease affects the ability of motor neurons to fire electricity, the team measures the electrical activity of the neurons. They also measure the function of the protein TDP-43, which is known to aggregate in people with ALS.

The final result will be a model that is representative of the irregularities and dysfunctions that happen across people living with sporadic ALS.

“The underlying question is, how different or similar are all these sporadic ALS patients?” Kiskinis said. “Our model allows us to ask whether the disease is driven by environmental factors or whether there is something about the genetic code of these people that makes them uniquely vulnerable to ALS.”

Research into sporadic ALS is especially important, since the vast majority of labs study familial ALS, said Robert Kalb, director of the Les Turner ALS Center at Northwestern Medicine. “Here, the researchers are taking a novel approach to model and study cells from individuals with sporadic ALS,” he said. “Using an innovative tissue culture system, this work may be able to define new disease mechanisms relevant to the most common form of the disease.”

The research, funded with a grant from the Les Turner ALS Foundation, is still in the information-gathering stage. Ultimately, the team hopes to test drugs in clinical trials on the cells to understand different therapies’ abilities to reverse or slow down the effects of ALS.

“Seed grants like this allow us to try out ideas that may or may not work,” Kiskinis said. “In this case, we have good evidence that this model we are building will be successful. So this grant allows us to generate key preliminary data so that we can pursue larger, multimillion and multi-year grants from the National Institutes of Health.”

Kiskinis, who has been studying ALS since 2008, said he was initially driven by scientific curiosity but now knows several people who have ALS. “At this point, it is personal,” he said.

“I get more and more hopeful each year,” he said. “The influx of money, people, and resources has been exponentially growing, and if we put enough resources into this, we are going to find solutions.”